How do we measure which regions are doing well? And what do we mean by “doing well”? Cohesion policy, which aims to ensure investment in less fortunate communities and reduce disparities between rich and poor, uses GDP per capita to decide where to throw its considerable financial weight. Although useful and straightforward, this measure only considers wealth, ignoring attractiveness and inequality.

The Regional Competitive Index (RCI) aims to capture in data the ability of a region to offer an attractive and sustainable environment for firms and residents. In practice, it’s strongly correlated with GDP per capita, but offers instead a broader measure of how favourable a region is to further development, innovation and a higher quality of life. The focus is on the potential for growth, and growth as a means rather than the destination.

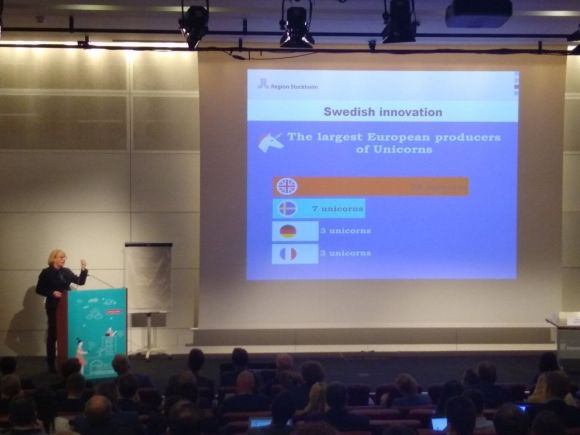

At the EU Regions Week currently taking place in Brussels, Marc Lemaitre, Director-General for Regional and Urban Policy at the European Commission, presented the 2019 edition of the index. It’s calculated from 270 regions in Europe and proposes regional scorecards which allow you to check how each region is performing in terms of 11 variables. These variables or “pillars” as the study calls them are diverse as macroeconomic stability, the strength of institutions, education and technological readiness. Top performers are often capital cities, especially those with world class universities, good connections and proximity to markets. Jostling for the top spots are Stockholm, London and Utrecht, with the Swedish capital classed as the most competitive region in Europe.

A model for European cities of the future

Enter the Mayor of Stockholm, Irene Svenonius, who took to the stage to present her investment strategies for her city with a certain amount of satisfaction. “Now all you need is the recipe of how we did this,” she joked. Her satisfaction is justified. She has a clear dual priority for her city which she has implemented them to great effect: public transport and public health. 70% of the archipelago’s inhabitants use public transport to travel to work with land-based public transport boasting zero emissions. Further to that, Sweden is a place where it is easy to start and close a business, fostering entrepreneurship. In part thanks to accessible, state-funded university places, people are highly educated with the capital drawing the best talents like a magnet. With regard to infrastructure, neither left- nor right-wing governments have allowed short-term political squabbles to stand in the way of long-term goals.

Overall, Svenonius manages the city with eyes on the horizon, assuming that, to make her city competitive, it has to be attractive. For her, that involves making people want to live there, helping them get around, giving them the tools to succeed through education, and keeping them healthy.

All this is rather humbling for London, where the number of people using public transport is dipping. An adult single fare costs double what it costs in Stockholm and the registration of private hire vehicles has risen 75% in 4 years, causing the sprawling English metropole to eye hikes in congestion charges. While the UK houses some of the world’s best universities, these are relatively elitist institutions with hefty fees. And perhaps we shouldn’t mention infrastructure where, in comparison to the long-term perspective of Sweden, Boris Johnson’s failed Garden Bridge project, which he planned during his time as London mayor, cost the UK taxpayer millions without ever being built.

Being competitive is about being attractive

London might be very nearly as competitive as Stockholm, but the impact of differences in governance shows up elsewhere. RCI is inversely correlated with inequality – meaning that the more competitive a region, the more likely it is to display high levels of equality between its citizens. While Stockholm is a relatively equal city, London is a staggering outlier lying miles outside of the trend by combining high competitiveness with massive gaps between the rich and the poor. Certainly, the exotic salaries from the global hub of finance, the City of London, are keenly fuelling this divide. Yet the extent of the gap is telling of different policy-making climate which allows wealth to be rapidly accumulated but stay at the top.

Svenonius emphasized that being competitive is about being attractive, and that green is not incompatible with growth. In doing so, the Swedish capital, whose high levels of equality are no coincidental consequence of its attention to health, public transport, respect for the environment and education, is a model of European cities of the future. Although it does not measure equality directly, the Regional Competitive Index encourages us to look at and aim for quality, not quantity. The full-time score is London 0, Stockholm 1.

Madelaine Pitt (West Midlands, UK)